from december 11-13, 2020, designboom partnered with bêka & lemoine to exclusively offer a free screening of ‘tokyo ride’. if you missed the online premiere, you can now watch the movie on the filmmakers’ on demand channel here.

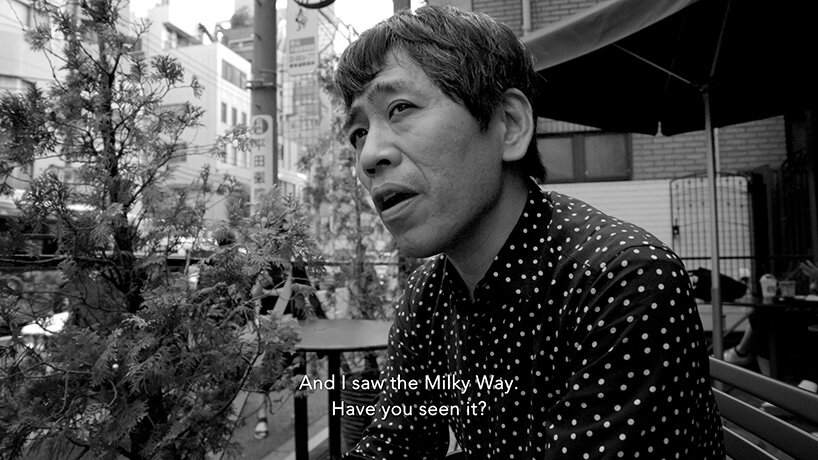

in ‘tokyo ride’ viewers are invited to take a drive through the city streets with one of japan’s most acclaimed architects. the movie immerses the viewer in the bustling daily life of the japanese capital courtesy of ‘giulia’, ryue nishizawa’s vintage alfa romeo. the movie is latest work by ila bêka and louise lemoine, two of the foremost architectural artists and filmmakers working today. the film was presented with the ‘artistic vision award’ at DocAviv 2020, before being crowned as the winner of the milano design film festival.

to learn more about the acclaimed film, designboom spoke with ila bêka and louise lemoine who discussed their relationship with ryue nishizawa and how his choice of vehicle, and even the unexpected weather, influenced the journey. read the interview in full below.

designboom (DB): why did you decide to make this film, and in what ways is it a continuation of MORIYAMA-SAN?

louise lemoine (LL): we were living in japan for six months as part of an art residency around two years ago. the film was shot then, but because of many issues, we’ve released it only now. this project with nishizawa-san was actually planned for a long time. we had met nishizawa about 10 years ago in france, where he was giving a lecture. at that time, he was very interested in making a film together and mostly about his house, ‘moriyama house’. so we discussed this — about two or three years ago — and we made the first film, MORIYAMA-SAN.

LL (continued): as usual in our films, architects are the most absent figures. we make films about architecture, but we never make the architect speak. with nishizawa, it was more about friendship in some ways. he was very happy with MORIYAMA-SAN, and we knew about his car and his love of alfa romeo. he promised to give this tour of tokyo in his car, and then we never actually did it. so, while we were in japan, we tried with his office to find a day to arrange this. but when you talk about a pritzker prize-winning architect, it’s always tricky to find a full day available. finally, we managed to find a date, and it was an incredibly rainy day as you can see in the film — not the ideal conditions to shoot a film in a very tiny car with no isolation from the outside.

DB: what aspects of ryue nishizawa did you think were appealing for the audience? what sides of his personality did you want to show?

ila bêka (IB): when we make films, it’s something very strange, but we don’t have an idea of what we want to do — it’s really total improvisation. in all the things we’ve made, it starts like this. we just have a desire to make a film about something. after that, we start to prepare a little bit in our mind. we never have a script, but normally we have a desire, and we start making a film. at the beginning, it was a problem to explain why we had the camera, but nishizawa was super cool. we just felt that staying for 12 hours in the city in a little car was a fantastic opportunity to bring a camera, and also to communicate this kind of experience that we had with him. we didn’t know how to film, what to film, or what to ask. we just wanted to share a moment with him… a very intimate moment.

IB (continued): we didn’t want to show his projects, and he didn’t want to either. it was very clear from the beginning that it was a meeting with a person, and not with a show — it was not representation. I think he’s the best architect we know in this sense, because architects always have this representational image. ryue nishizawa is so honest and modest that he accepted the idea of just making a film about everyday things. we were really surprised by this and very happy also, because it’s just like talking to a friend. I think the beginning of the film was really important for instilling this kind of atmosphere, because of the rain, which was very unpredictable. the problems that the car has with the rain and opening the windows… it instilled right away a sort of informality, not in control by him or us.

LL: I think also this challenge was particularly interesting, because obviously when we had the idea, it was more of a hypothesis or a challenge, but we didn’t know if it would succeed. we spent six months in japan learning how to communicate or create some bridges of communication. we thought that it would be extremely interesting to propose this experience to nishizawa. in terms of public figure, SANAA, as as a duo, is extremely in the distance. you know the work, the office, you may have attended some lectures, but they do not expose anything about themselves as individuals. it’s a sort of ethereal, conceptual representation.

IB: there’s a lot of control in japan. they like to make things perfectly. there’s not a lot of space for improvisation. we work always with improvisation, so it’s not easy to find people that are ready for this.

LL: it was a surprise and a real pleasure, to establish this game of spontaneity — what you make out of this challenge. it’s almost a performance in some ways, to understand what you could get out of the experience of being enclosed in a small car for almost 12 hours. it’s the idea of creating a psychological portrait of someone, but it’s thanks to time and thanks to this sort of intensity of the relationship that you get to open it up.

DB: so it’s a road movie with no specific destination in mind…

IB: it’s a wandering, a psychological wandering.

LL: the destination is this psychological opening. it was the only aim actually.

DB: you mentioned the challenges of filming in such a small car…

LL: something that we found out afterwards is that he chose this car on purpose, because he has another one, or a couple of others, that we could have taken for the day. but for him, he thought that this model was particularly adapted to this challenge because of its scale and it being so tiny. it created the perfect conditions for intimacy. that’s extremely interesting, because if we were in a van or something, where there was more of a distance between people, probably this sort of magic alchemy may have not worked in the same way.

IB: there’s also the thinness of the car. it’s very thin. you are in a car, you are in a very intimate place, but in another sense, you’re very close with the city. now you have very big cars that when you are inside, you’re totally isolated from the city. so, this is a really interesting idea that nishizawa has about cars, and the spacing between inside and outside.

LL: for instance, for us as europeans, the question of heavy rain that changes all your plans, your itinerary etc. — it could have been understood as one of those bad and unpredictable things that totally changes everything. however, when we discussed with nishizawa, his extraordinarily delicate and poetic mind perceived the porosity of the car as a good quality rather than a defect, because you can perceive the elements. you are in contact with wind and water, and you can feel the speed. that’s very much in the japanese spirit.

IB: that’s also true in MORIYAMA-SAN, because the kind of life that mr. moriyama has in that house is totally related to that feeling. he has a bedroom that is separate from the bathroom, from the kitchen, and from the rest of the house. he is always outside. in the summer it’s very hot, and in the winter it’s very cold, but he has to go outside to live. he lives in a house that is outside and inside.

DB: in what ways did the car as a vehicle show tokyo, and let viewers experience the city?

LL: it’s not so common to go through tokyo by car — because of the size, because of the scale, being the biggest metropolis in the world. the city is more typically understood by train or other modes of transportation. this reconfigured our understanding of the city, because we went on highways and discovered a new temporality of the city, and new paths more unusual to the common tourist in tokyo.

DB: could you speak about filming in black and white and what kind of qualities you think that brought to the film?

IB: we didn’t know that we wanted to make a film in black and white. we shot in color obviously. we like japanese cinema, and we had a lot of references from japanese cinema from the 60s or even before, by kenji mizoguchi and akira kurosawa. some japanese street photography was also very important for us as a reference.

LL: it also suited the time of the [alfa romeo] giulia in some ways. it was for giulia and also for these references of street photography, with a very strong contrast in black and white. also, the architecture of SANAA is almost an architecture of the subtleties of grays, and the variation of the grays. it’s not so much an architecture of color. we thought it suited the project in many ways.

DB: what do you hope people take away from watching ‘tokyo ride’?

IB: it’s a film like all our other films. if you watch this film with the intention of finding out some information about architecture, you will be frustrated. it’s not a film about information, it’s a film about about an experience and about an atmosphere — a japanese atmosphere. obviously you also have some information, but it’s intimate information from nishizawa about life. if you’re ready to open yourself up, to enter the car, and to feel the experience and atmosphere that he’s able to create with his memories, you’ll find a man that is opening his heart in a very particular atmosphere. if you are able to open yourself up to understand this, I think you can appreciate it.

LL: I think in that sense, the film is very much a road movie about a drifting experience. the movement of the car brings you somewhere, you don’t know exactly where, and this is the experience the film tries to create — that you are on a psychological journey. what I think differentiates this film, compared to a classical portrait of an architect, is that you are able to enter the difficult-to-access intimacy of an architect, rather than the little paragraph of a bio that you can find on a website or wikipedia. this is far from the aim. what we try to bring out is that very difficult-to-access space, which is the territory of intimacy.

project info:

name: tokyo ride

directors: ila bêka & louise lemoine

director of photography: ila bêka

editing: ila bêka & louise lemoine

colorist: melo prino

sound mix: walter amati, fuji studio

production: bêka & partners, france

japan, 2020, HD, B&W, 90 min

BêKA & LEMOINE (8)

DBINSTAGRAM (2250)

RYUE NISHIZAWA (25)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.