NEO HERITAGE: Defining contemporary African architecture

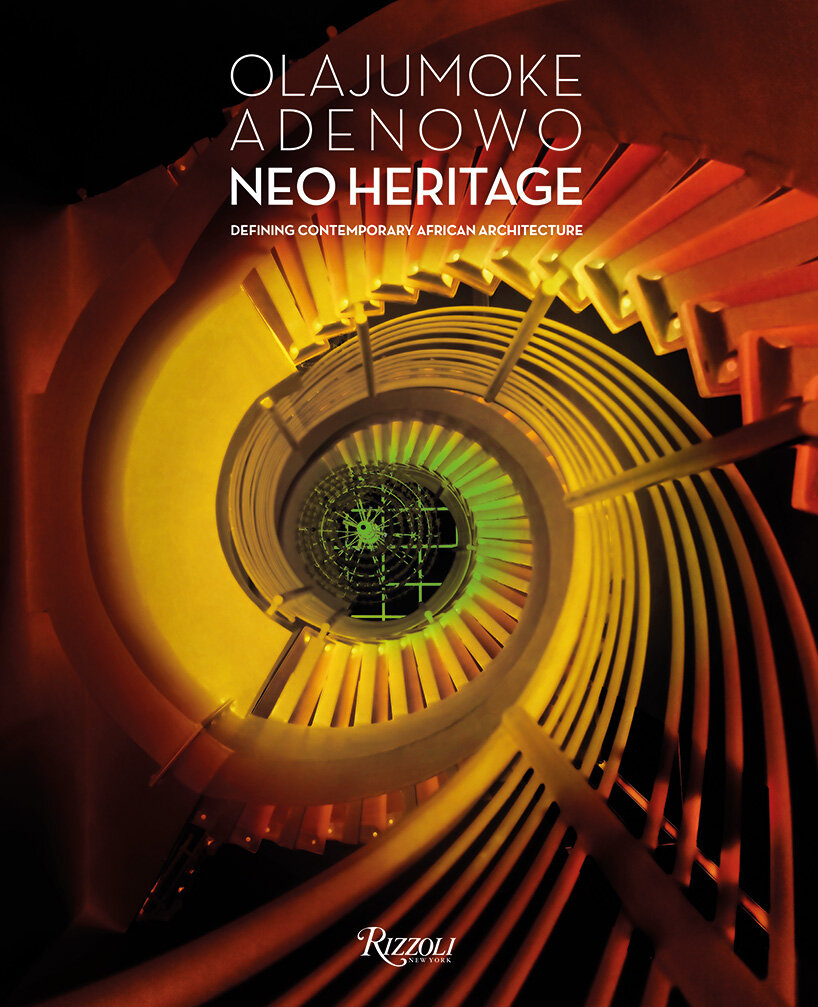

Olajumoke Adenowo, recognized as Africa’s most influential female architect, introduces her new book titled NEO HERITAGE: Defining Contemporary African Architecture. Published by Rizzoli New York, this comprehensive volume presents Adenowo’s unique vision and perspective, introducing her thesis of Neo Heritage which is rooted in African heritage design principles, and offers a new conceptual framework for global advancements in the field of architecture. With ten captivating chapters, the book delves deep into the theme of Neo Heritage, exploring its defining characteristics and implications.

Starting from an analysis of traditional African architecture, Olajumoke Adenowo derives principles that transcend the various styles, types, and locations of African heritage architecture, ultimately guiding the future of contemporary African architectural thinking. In an interview with designboom, Adenowo, also referred to as ‘Africa’s starchitect,’ discusses her Neo Heritage thesis, the concepts of beauty and aesthetics, the influence of light, and the significance of decoration and functionality in African architecture. Read the full discussion below to discover more about Adenowo’s insights and creative philosophy.

the palace of the Emir of Zaria-Zazzau in the Hausa architecture style | image by Taiwo Aina

interview with Olajumoke Adenowo

designboom (DB): Can you elaborate on the concept of Neo-Heritage and how it redefines contemporary African architecture? How do you envision it contributing to global architectural solutions?

Olajumoke Adenowo (OA): To a large extent, examples of post-colonial or ‘contemporary architecture’ that seek to learn from heritage architecture on the continent have leaned heavily on mimetics that is, copying the external and interior forms of traditional African architecture. Neo Heritage is a radically different approach: My Neo Heritage ideology is based on principles I have derived by analyzing sub-Saharan heritage architecture in light of the relevant interdisciplinary ecosystem that birthed the architecture. The ecosystem is comprised of physical and non-physical contexts such as the physical contexts of climate and geography, the non-physical contexts of the ethno-cultural and socio-economic matrix, the history, etc. From my analyses, I derived seven principles of my ideology which I have tested in my practice for decades – Neo Heritage which I hope can guide contemporary African architecture.

Principles go way beyond mere formalism; these principles allow each architect to express their own creative solutions in diverse forms as guided by these principles. I intentionally ideated from African heritage design principles which are globally relevant and universally applicable to contribute to solutions to global challenges in the architectural space. African Heritage Design solved key issues the globe faces now such as sustainability, inclusive design, cultural identity challenges, and several social issues. Neo Heritage leverages my roots in my heritage and my global exposure to present my learnings from African heritage design to the globe.

Friday Mosque Zaria by Babban Gwanni intterior | image by Taiwo Aina

DB: The book emphasizes the importance of beauty and aesthetics in African architecture. Can you share specific examples of how beauty and aesthetics shape architectural design in Africa?

OA: Function was the primary driver of African architecture. Form actually followed function, but it would take minds thoroughly steeped in the multidisciplinary ecosystem that produced the architecture to understand the purpose for which the designers ornamented the built forms and spaces. I have observed that Africans did not have ‘art for art’s sake’. Their approach to aesthetics is what I have termed Functional Art. They adorned objects, buildings, even their bodies and faces with a clear purpose; ranging from -identity, signifying status, branding, documenting a narrative, for worship, as an invocation etc.

Many Western scholars have misunderstood such topless female figures as depicting the king’s wives, but anyone steeped in Yoruba culture would know the King’s wives are never depicted topless or nude. The carved caryatids of kneeling topless women holding various objects such as fans in the courtyard of the ancient palace at Idanre, Yoruba land in South Western Nigeria were visual invocations of women at the height of their powers (kneeling evoking the birthing position) blessing the palace, the King, the people, and the land.

AD Consulting Studio by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Kelechi Amadi

(OA continued): The Mbari houses in Igbo land, Nigeria, with their sculptures of the deities and the people posed in diverse scenes were not only a propitiation to ‘Ala,’ the female earth deity, but also a depiction of the Zeitgeist. In many cases, the deity was depicted as evolving in her lifestyle and adopting many new devices introduced by the colonial powers for instance using a telephone or being attended to by a secretary, exactly like the colonial District Officer! The corollary to this concept in Rome would be to depict Juno using an iPhone 14 pro-Max! This was a truly ingenious reflection of the Zeitgeist showing that the African society then (as now) remained open to new concepts and ideas in a delicate tension to preserve what it perceived to be its core essence. Outside Nigeria, the vividly painted walls of the Ndebele in South Africa were conceived not as mere frescos or graffiti but as ethnic identity brands. The walls of the buildings in traditional Hausa architecture in the North of Nigeria were adorned with bas reliefs which were insignia of the status, the trade, and the occupation of the owners. The scale and complexity of the ornamentation in many cases alluded to the wealth and status of the inhabitant. African aesthetics and beauty were dictated by function, albeit a function that could only be deciphered by insiders.

AD Consulting Studio by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Kelechi Amadi

DB: In the context of traditional African architecture, how do decoration and functionality intertwine, and how can this relationship be relevant to contemporary architectural practice?

OA: Adolf Loos said ‘Ornament is a crime’. I can safely say that Africans do not believe this to be true! In a principle I have termed Functional Art, I note that African peoples’ approach to ornamentation was ‘Ornamentation with a function’. Ornamentation for African traditional designers was for branding, a celebration of identity and cultural heritage, and in many cases, it also served to communicate an intangible Fourth Dimension as I term the phenomenon of invoking an intangible deep emotive connection to the forms and spaces like in the Friday Mosque in Zaria.

In my architecture, I deploy functional art as part of the Gesumtkantswerk (total work of art) that is integral to the core of the design itself in my work, like the mosaic I conceived for the water feature in the garden of the Reeve Road villa which functions not just as a beautiful water feature but is a visual narrative celebrating the head of the household in his dual role as the head of the extended family. In my contemporary African architecture, the principle of Gesumtkantswerk means that functional art is integral to my architecture. I believe that contemporary African architecture would serve our societies well by embracing the traditional design; ideation principle of functional art integral to the whole (and not an applied afterthought) which connects the people to their heritage in a meaningful manner.

villa at Reeve Road Ikoyi Lagos by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Emmanuel Oyeleke

DB: The influence of light is highlighted as a significant aspect of African architecture. How does light, both in physical and cultural contexts, shape architectural expressions in Africa?

OA:Traditional African architecture was practiced before the advent of electric lighting in the late 1800s. As a result, the forms and spaces were conceived following the diurnal and nocturnal cycles. Their sustainable approach to life and architecture, which relied on natural light during the day rather than fossil or vegetable fuels, led to the optimization of daylight. Spaces designed for optimal task lighting were open to the sky in suitable weather conditions. For spaces requiring shelter, such as kitchens, they were located in the eaves surrounding open courtyards or partially enclosed spaces in areas where protection from the weather was necessary. Spaces dispersed around the courtyard or compound were typically used for mono-functional activities like sleeping and other nocturnal tasks. These spaces were relatively dark, with high windows in the walls to prevent pests or predators from entering. The plan form and fenestration arrangement, which are integral to the external morphology of the building, were influenced by the need for access to daylight.

Regarding the cultural significance of light in heritage architecture, it is observed that light streaming from above is deeply connected with social and ceremonial gatherings. Large reception halls with clerestory windows or courtyards in traditional African buildings served as gathering places, likely due to the ample daylight provided for such occasions. A Yoruba proverb states, ‘Oru o mo eni owo’ – meaning ‘all manner of atrocities can occur to anyone, even the honorable, in the dark’.

villa at Pinnock Beach Estate by Olajumoke Adenowo – roof terrace at night | image by Emmanuel Oyeleke

(OA continued):

In contemporary times, it is not uncommon to witness buildings designed without considering the potential of daylight for passive lighting. This is one of the issues that Neo Heritage aims to tackle. In my own architectural practice, guided by the Neo Heritage ideology for decades, light plays a primary role. While heritage architecture relied on the compluvium for both light and ventilation (due to the structural challenges of creating large windows in adobe walls), I approach the design of courtyard spaces by separating their dual functions of illumination and ventilation. As a result, my buildings feature large windows on the wall planes and sizable extractor fans (to facilitate a stack effect) for ventilation in atria like the GLA main auditorium. Meanwhile, the direct overhead light, traditionally associated with assemblies, celebrations, grand receptions, festivities, congregations, and grand entrances, continues to provide illumination from above in the grand auditoriums and entrances of my buildings.

Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife by Arieh Saron – view across the quadrangle towards the Secretariat building | image by Folarin

DB: When it comes to climate-responsive design, what are the unique challenges and opportunities faced in Africa?

OA: The first challenge that comes to my mind is the tendency to ignore our climactic context and fall into Neo-Colonialism or perhaps even misunderstood globalism, by cutting and pasting architectural solutions from very dissimilar climactic contexts and trying to implement them in our locale regardless of their environmental peculiarities. I believe that even if the world is a global village, every village still has unique neighborhoods. The whole world can’t look the same.

As a result of post-colonial ‘contemporary architecture,’ hermetically sealed glass buildings that require ventilation, cooling, and heating, relying heavily on electricity, can be found throughout sub-Saharan Africa. This missed opportunity is disheartening, considering that most of sub-Saharan Africa experiences favorable weather conditions, characterized by mild winters and summers. Designing buildings that draw inspiration from the heritage design of the respective locations could easily accommodate these climatic conditions. However, there is a deliberate reliance on electricity and fossil fuels, disregarding the potential for passive ventilation, heating, and cooling systems, similar to those utilized by African ancestors. This trajectory leads sub-Saharan Africa down the same path of development as the global north. Considering the significant growth lying ahead for Africa, with the world’s largest young population, the implications for climate change are potentially disastrous for the entire globe.

Guiding Light Assembly Ikoyi by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Kelechi Amadi Obi

DB: How can the principles of circular economy and material reuse be effectively applied in African contexts?

OA: As Africans, the challenge lies in recycling our waste into useful new materials, just as our ancestors did, and scaling these solutions to meet present and future demand. The fact is that because of the level of research and development involved, this is a policy issue. Secondarily, it’s also an issue of the Zeitgeist; the aspirations of the people must be molded towards celebrating and adopting solutions evolving from Africa. We have to develop homegrown alternatives and take pride in our own solutions, although in the short-term, this might upset the prevailing global balance of trade as Africa is considered the next big market and it’s tempting to keep proffering ill-fitting solutions developed for other contexts to Africa. In the long term, however, it is in the interest of the whole world for Africa to develop the confidence to evolve its own solutions and do so right now. Africa has the largest youth population in the world, and we can only avoid sinking as a planet if Africans change their paradigm of consumption. At a global level when we consider Africa we need to shun short-term gain for long-term benefits.

AD Consulting Studio by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Emmanuel Oyeleke

DB: How do Nigeria’s ethno-cultural context and physical realities influence architectural expressions, and how can these insights be applied to the wider African continent?

OA: Every expression of architecture and building type, or architectural style, is solving for the ethnocultural context and physical realities of the locale as the inhabitants seek to shelter their human activities. The ethnic-culture and physical constraints of an environment are the matrix of a people’s architecture and Nigeria is truly unique in its ethnocultural and physical diversity; the ethnocultural front; Nigeria consists of over 500 ethnic groups with distinct languages and cultures and its physical contexts is one of the most diverse geographies in terms of vegetation and climate. The physical environment dictates available materials; and consequently, climate, geomorphology, geology, and geography in its entirety play a huge role in traditional architecture. These two factors apart from the interphases with the rest of the globe in ancient times and directly influences its diverse architectural expressions which ( or one country) is vast in terms of forms, materials, and technologies.

This serendipity of factors makes Nigeria a rare crucible of learning for deriving principles that transcend skin-deep formalistic expressions. Principles are foundations for thought that transcend peculiar contexts, in its rare and extreme diversity of ethnocultural and physical contexts Nigeria presents a unique opportunity to probe beyond the diversity of mere formalistic expressions and derive principles that hold true in every context and are therefore applicable in every context and therefore can be applied across sub-Saharan Africa and the globe.

atrium in the Rain Oil Headquarters by Olajumoke Adenowo | image by Emmanuel Oyeleke

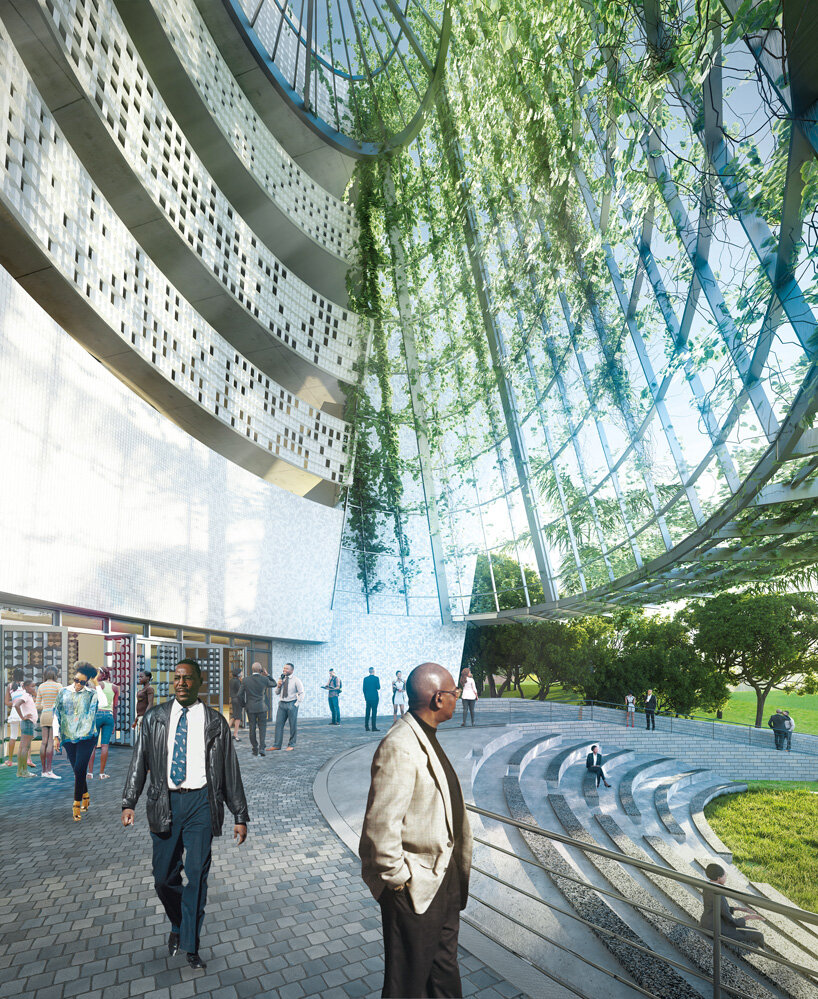

OAU Senate building project Ife by Olajumoke Adenowo | image courtesy of AD Consulting

the cover of NEO HERITAGE: Defining Contemporary African Architecture | image courtesy of Rizzoli New York

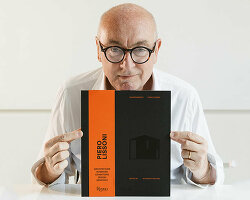

portrait of Olajumoke Adenowo

project info:

name: NEO HERITAGE: Defining Contemporary African Architecture

author: Olajumoke Adenowo | @jumokeadenowo, founder of AD Consulting

publisher: Rizzoli New York | @rizzolibooks

DESIGNBOOM BOOK REPORTS (182)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.