Phillips auction house opens its new space in milan

London-based auction house Phillips has opened its new location in Milan, right in the heart of the city on Via Lanzone, between Via Circo and Piazza Sant’Ambrogio. Just a stone’s throw away from the Cathedral of Duomo, the expansion signals Phillips’ commitment to Italy and investment across Europe, broadening its presence by opening its doors in one of the world’s cultural capitals. The Milanese home of Phillips – which includes an office and gallery in which to host curated exhibitions, previews, and exclusive events – was marked by an exhibition between September 13th to 15th where designboom had the chance to speak with Domenico Raimondo, the Senior Director, Head of Design in Europe and Senior International Specialist of Phillips, who told us about the significance of the new Milanese space and the events and processes that may take place when Phillips prepares for an auction.

These showcased artworks in Milan during the opening will also be featured in Phillips’ respective October and November 20th Century & Contemporary Art auctions in London and New York. On October 31st, Phillips will highlight selected and rare works of 20th and 21st-century French, Italian, Brazilian, contemporary, and Scandinavian design for its London Design Auction, with a preview at Phillips’ London galleries on Berkeley Square from October 25th to 31st. Immediately following, a group of works by Lucie Rie and Hans Coper will take the auction stage on November 1st, 2023, at Phillips’ Berkeley Square location. Phillips states that this will be the most significant collection of Lucie Rie and Hans Coper to ever come to auction, originating from the Estate of Jane Coper and the former Collection of Cyril Frankel.

During the inauguration of the Milanese space, designboom sat down with Domenico Raimondo to talk about Phillips’ new home in Milan and more. In the interview, he shared insights about what the new Phillips location means for the auction house and the process and development that take place when Phillips hosts bidding and design events. Read on to learn more.

Phillips Auction House space in Milan | photos © Ugo Dalla Porta

Interview with Domenico Raimondo of Phillips

designboom (DB): Can you tell us about your official role and background?

Domenico Raimondo (DR): My current role at Phillips is the Head of Design in Europe. I have a background in architecture and graduated from the Architectural Association School of Architecture where my external examiner was Rem Koolhaas. He liked my project and asked me to go and work at OMA in Rotterdam, but I found life in Rotterdam a bit too harsh, so I left and moved to New York after six months to work on a project with a close friend who had just graduated from Columbia University. When it finished, we came back to London and opened an office with another friend.

During this time, I also started teaching in a studio (ADS3) in the architecture department at the Royal College of Art in London. I taught there for eight years as well as being an invited guest to various other universities. Eventually, I decided I wanted to stop practicing as an architect, so in addition to teaching, I started working at Gordon Watson. A friend suggested I meet up with Alexander Payne, who at the time was worldwide head of Design at Phillips. After our meeting, I was offered a position. Somehow, through a series of events, my career took different directions, it might not seem quite a linear path, but it makes sense to me. I think architecture encompasses a lot of other disciplines that are part of our environments. It’s a matter of (different) scale.

London-based auction house Phillips has opened its new location in Milan

DB: You recently opened a place of Phillips in the central and historic yet modern part in Milan. What is the concept behind this place?

DR: I think that in terms of being a nation with a strong link to design, Italy is crucial, and Milan is the center for design within Italy. Wiener Werkstatte, the Bauhaus, French design and so are Italian design. Both pre- and post-war, Milan is pivotal within the Italian landscape. Phillips is recognized for our association with Italian design, and it’s where we source most of the material for our sales, so to speak. Most of our lots come from Italy. Incidentally, we found this lovely place that feels a bit like a domestic setting where people can gather, exchange ideas in a relaxed manner, and showcase works of art and connect.

So in that context, it’s an ideal setting. The sixteenth-century palace, designed by Giuseppe Meda, underwent an intense interior renovation (after the Second World War), thanks to the intervention of the architect Luigi Caccia Dominioni. To preserve the building’s architectural legacy, Phillips collaborated with Caccia Dominioni’s daughter and granddaughter in identifying period design elements and furniture that reflected the illustrious Milanese architect’s original design.

DB: Will it be open to the public or by appointment only?

DR: At the beginning by appointment only, but eventually it will be open to the public or by invitation. The idea is to host different kinds of exhibitions and events to activate the space and make it alive during the year.

the location is right in the heart of the city on Via Lanzone, between Via Circo and Piazza Sant’Ambrogio

DB: Can you tell us more about your interest in Italian design?

DR: What made Italian design different from all the others was that the players were latching onto the industry to promote the idea of ‘democratic beauty,’ where everybody had access to design, thus improving people’s lives. We continue to lead the Italian Design market, holding some world auction records. We have promoted the work of Italian architects and designers, including Piero Fornasetti, Gio Ponti, Carlo Mollino, Gino Sarfatti, Ettore Sottsass, Jr., Carlo Scarpa, and many others.

For example, the glass market as we know it now started with our sale of a selection of works from the Venini archive in 2009 in New York. Since then, we have done many initiatives to promote and expand the Italian design market. Gio Ponti, for example, created beautiful commissioned pieces, which served as inspiration and were then used to create a production that was simplified and rationalized for the masses through industrial production.

Ponti (and Pietro Chiesa) began making high-end furniture using industrially produced glass. This was incredibly relevant. At its core was the idea of democratically distributing the benefits of industrial design. His relationship with Fontana Arte was also partially about that, where he would design unique pieces for important commissions, which in turn would inform industrial production. He initiated that process and throughout his career kept going back to Fontana Arte to test things and bring them back into the world of ‘value solutions’.

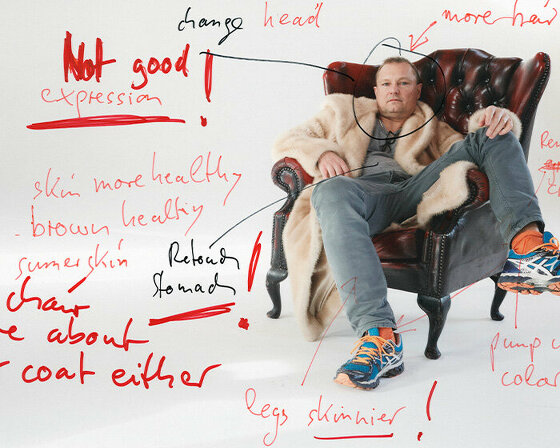

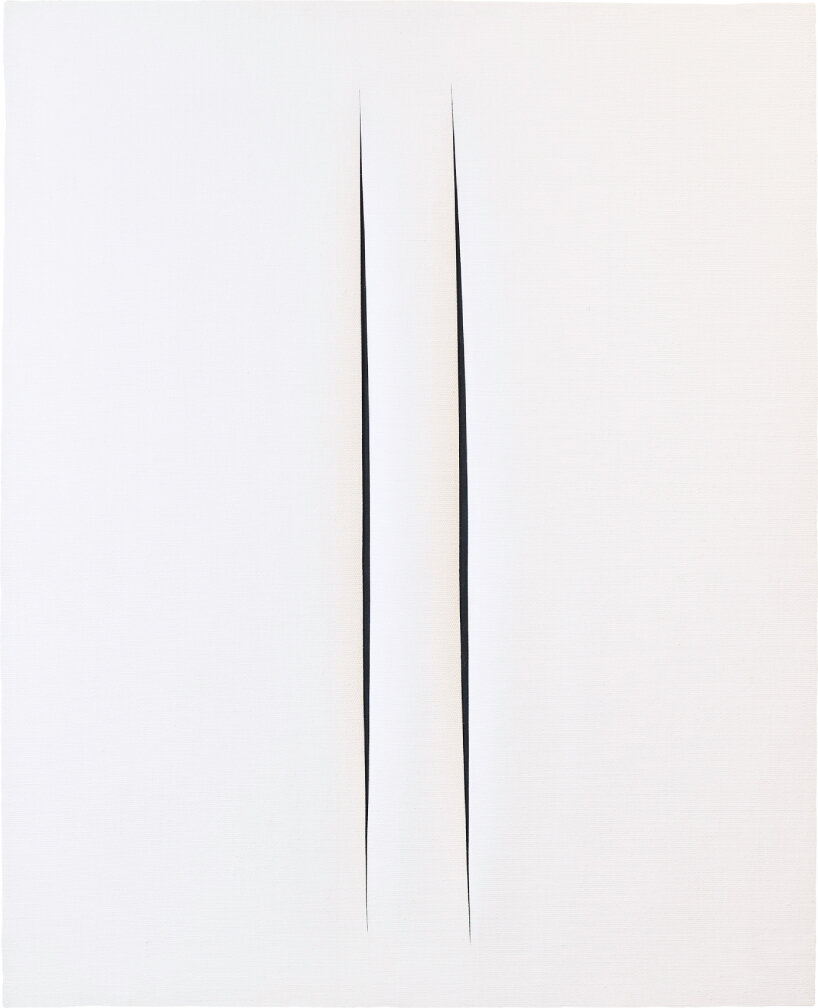

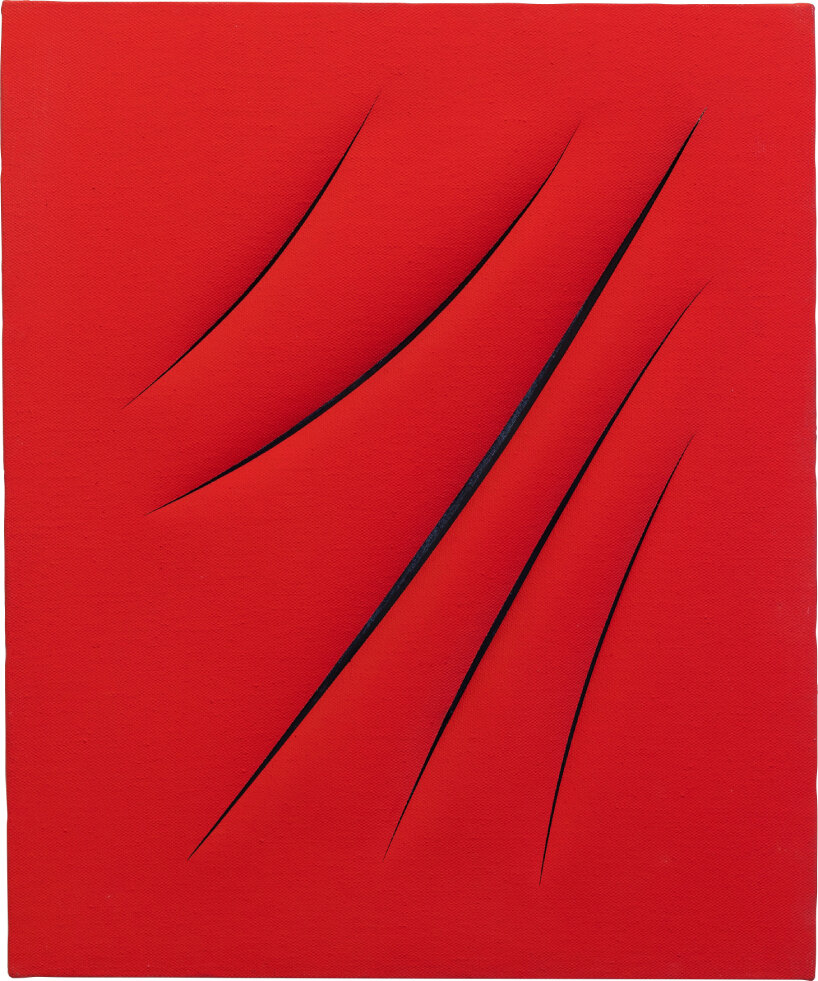

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, Attese | photo © Maria Moratti

DB: Where do you draw the line for contemporary design? Commissioned one-off and limited editions?

DR: The design market is always shifting. At a certain point, the term ‘Design-Art’ was coined, which could be seen as a bit of a contradiction. Around 2005 and 2006, there was a boom in limited editions, which were presented with high estimates and reached high results at debut auctions. But the financial crisis of 2008 came, and everything kind of collapsed, partly because it wasn’t a market with as many players as the contemporary art market.

I’ve always been interested in contemporary design. Phillips started that market, and many galleries are moving in that direction. I understood then why. They have complete control over it, including the pricing, and it gives them a unique identity. Personally, I don’t really have any reservations per se; I tend to draw the line when I see something that I may find repetitive or derivative in an unimaginative way.

these showcased artworks in Milan will also be featured in Phillips’ respective October and November auctions

DB: It might be complicated to get a full picture of the value of certain pieces. Let’s say there are prototypes and models, then the first production series. And we can think here also of things that have been historically produced over years. Is the last piece of similar value to the first?

DR: There is also the issue of fakes, but that’s another aspect. If something suddenly commands high results, and suddenly many examples appear on the market, alarm bells go off. It’s our responsibility to ensure that we offer material that is authentic. It’s challenging. Authenticity and traceability are fundamental principles in our auctions. We are extremely rigorous in ensuring that every piece we auction is original and not a fake.

Rare objects of the highest quality, in good condition, and which have not been overly restored attract great competition on the market and inevitably sell well. Within the landscape of design, both pre-war and post-war, research and learning about these pieces naturally lead to selections based on what is more or less expensive.

DB: Do the market’s forces also come into play?

DR: We don’t control the market; we are only a part of the equation. When we value an item, we must make it attractive to draw in bidders and stimulate competition; it’s a fundamental strategy for auctions. Phillips’ Design department, which was founded in 1999, focuses on the last two centuries, showcasing the best of modern and contemporary design. We obviously try to be in tune with the market and what clients’ desires are. It’s fascinating how this conversation takes place in the marketplace as tastes evolve. We naturally start from the early 1900s, and as collectors’ preferences evolve, so does the conversation.

As a department, we are maybe less focused on trends; rather, we take pride in looking at the relevance of a specific work within a historical context, whether it’s past or present. I have clients who have become really interested in Radical Design. One, in particular, a wonderful collector, whose taste and preferences have, and still are, evolving very rapidly. When she started, we were looking at Design from quite a specific modernist point of view. Now her focus has broadened, and she is also very engaged with Radical Design. I think it’s a natural evolution for an intelligent person who is interested in the context and the evolution of design.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, Attese | photo © Maria Moratti

DB: Does that mean that the idea behind the collections is to have design pieces to live with?

DR: I think so. Most of my collectors/clients buy with a place in mind where they can display and live with the work. I think of Francesco Carraro, who was one of the great collectors; his collection was truly fabulous. When you visited his apartment, it was an incredible experience. Everything was beautifully displayed in his living rooms and bedroom. He lived with his collection.

Most of the collectors I’ve worked with are like that. They live with their collections. Sometimes they say they don’t have enough space, but the best collectors always find a way to make room. They keep building up their collections. This is why Francesco’s collection became sublime by the end of his life. When he found something better, he let go of the lesser one. It wasn’t about acquiring in an orderly fashion; it was about refining the conversation.

DB: Are you also curating exhibitions?

DR: Personally, I don’t curate or get directly involved. I’m part of the market, not the one curating it. But in the past, some prominent Italian manufacturers I’ve worked with offered some of their works at auction and asked for suggestions on interesting names to collaborate with on special projects. At the time, I did suggest some names, and I think some of these might have evolved into something more concrete, while others didn’t. So, while I’m open to offering thoughts and ideas when asked, I don’t consider myself a curator, nor do I believe it to be my role.

exhibition view inside Phillips Milan

DB: Do you see the initiatives of Phillips as different from other auction houses? Do you see an identity that stands out?

DR: The first auction house to use the term ‘Design’ for their sales was Phillips; before that, they were always referred to as ‘Decorative Arts.’ This started in the early 2000s, maybe even the late ’90s. Since then, there has always been a strong emphasis on Design at Phillips. At the time, Christie’s was also an auction house that had a substantial selection of design pieces, but it was presented under the umbrella of ‘Decorative Arts’ with other, perhaps more decorative, material.

I think our identity lies in continuously evolving and staying ahead of the trends. It’s easier to follow the crowd, but it’s far more intriguing to set the trend and watch it evolve. That’s where the real difference lies. Adding surprises to the conversation can make people see things differently, especially in an era where everything seems superficial and lacking depth.

DB: It may be noticeable that digital communication is handled differently among auction houses.

DR: We’ve moved away from producing physical catalogs and increased our online presence. We provide a digital catalog that you can access to get a sense of our current direction. The layout of this digital catalog is important to me. Whether it’s being viewed by 10 people or 10,000 people, what matters is the quality and flow of the presentation.

the expansion signals Phillips’ commitment to Italy and investment across Europe

DB: Because the pieces are related to one another?

DR: I believe that how you arrange things is essential. It forms a core structure. It’s a visual representation of ideas and thoughts that are connected. This is crucial to me. Phillips has decided to stop printing catalogs, but I still believe that how you organize a sale and present it in a digital catalog is important.

DB: Do you think there is more education needed in this industry compared to other markets? Also, how big is the market of design for Phillips compared to the other sectors?

DR: I believe that education should be ongoing, in every field and market. Even in large markets like ours, which are financially significant, education is crucial. In fact, in such markets, there might be a greater need for education to prevent speculative activities. We live in an era where continuous learning is essential.

I can’t provide specific statistics now, but someone once told me that we don’t lead in terms of market share, but rather in terms of ideas. While I’m not sure if that’s entirely true, I would like it to be. Sometimes it’s about how you want to present yourself and your values. Education is important because it keeps us all learning and questioning things, which is vital.

exhibition view inside Phillips Milan

DB: Onto you, can you share your daily routine with us? How does it look like?

DR: In my job, I often call and talk to clients. This doesn’t always lead to a transaction of any sort, whether it’s a consignment or a private sale, and that’s okay. I really enjoy these conversations; I prefer them over sending emails. I also like meeting people in person. It’s nice to sit down with them and have a chat. Some sellers come to me regularly because we have a good relationship, and they might seek advice, while others might come through referrals from previous clients. There are private clients who know they own an important piece; I meet with them even if they’re not ready to sell. It’s a privilege to view these items and meet the people behind them. This is something that’s a part of what I do and something I love about my job.

DB: Does it happen that you have to compete with other auction houses?

DR: It is often competitive in this field, and I don’t particularly like that. It’s not that I dislike competition itself, but when everything becomes solely about the market and money, it’s unhealthy, particularly if it starts a bidding war between competing auction houses to try to win the piece for auction. This is because it might end up backfiring if the piece is presented with an inflated estimate and might end up unsold. In those situations, I try to take a step back and ask if we can just have a genuine, straightforward, and realistic conversation with the client. It’s about keeping things human. If they understand, great. If not, sometimes it’s good to walk away. Ultimately, it’s also about protecting the market and the client from creating false expectations and bubbles.

François-Xavier Lalanne, ‘Grand Bouquetin’, 1999 | patinated bronze; produced by Fonderie d’Art Bocquel, Grainville-Ymauville, France. Number 1 from the edition of 8. Proper right front hoof impressed 1/8 and incised fxL. Proper back left hoof incised with foundry mark bocquel Fd.

DB: When people come to you, do they ask for estimation?

DR: When it comes to selling valuable items, there’s a lot of planning involved. We aim to be cautious in our estimates to ensure we get the best outcome for our clients. Sometimes, clients understand this approach, and everything works smoothly. Other times, clients may expect more money, and if, in our opinion, the expectations are unrealistic, we need to say that we don’t advise selling at that level. It’s all about trying to get the best deal for both the client and us.

However, some clients may resist this approach, thinking we’re trying to get something valuable from them for too little. They forget that we’re not buying; we are selling on their behalf. Our role is to help them get the most out of their property. So, it’s important to communicate and make sure everyone understands the process. In the end, it’s about making the work as attractive as possible to potential buyers while being fair to the client. Sometimes, when negotiations start, emotions can come into play, and things can get a bit more complicated.

DB: Are you more interested in bigger pieces?

DR: Big-value pieces are great because they can bring in substantial value. They’re like the main ingredients of a cake. However, I’ve also come across small and seemingly low-value items that, to me, are incredibly important within the context of a sale or a conversation. They might not be the starting point, but they add something unique and special to the overall picture. It’s like finding a missing piece of a puzzle that completes the picture.

Ettore Sottsass, Jr., Rare ceiling light, model no. 12625 designed 1956 | acrylic, brass, painted brass; manufactured by Arredoluce, Monza, Italy

DB: When is the next auction coming up?

DR: October 31st, 2023 in London. It is our various-owner’s sale followed by a ceramic sale on November 1st with a selection from the estate of Jane Coper and the former collection of Cyril Frankel. These will be all Hans Coper and Lucie Rie pieces.

DB: How do you feel when you let these nice pieces go to the highest bidders and not own them?

DR: People often ask if this job feeds my desire to own things. Well, it’s a bit different. You see, people entrust me with these incredible items, and I get to study them for a bit. I research them, talk to other experts, and uncover all the details, like the history, the techniques used, or even the stories of the families behind them. It’s like indulging in a feast of knowledge and passion.

Then, when I’ve absorbed it all, I can let them go. I get to have them for a while, appreciate them, and learn all about them. You often fall in love with something at the start of the process. But eventually, I let them go. There are some items that have become a part of my life, hidden away in the corners of my memories. As a result, I don’t really want more stuff to carry around in life. My job fulfills my desire for possession. It’s a tremendous privilege.

left to right: Domenico Raimondo, Margherita Solaini, Cheyenne Westphal, Carolina Lanfranchi | photo by Alto Piano Studio

project info:

head of design, europe: Domenico Raimondo

auction house: Phillips

EXHIBITION DESIGN (507)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.