US Embassies of the Cold War – architecture as a diplomatic tool

During the Cold War, the US Department of State wielded modern architecture as a powerful tool of cultural diplomacy. Crafted by renowned architects such as Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, and Edward Durell Stone, these embassies were designed to convey American ideals of progress and democracy. Strategic use of modernist principles resulted in functional, welcoming, and visually appealing structures, featuring elements like glass, steel, open layouts, and expansive windows. Beyond their physical attributes, the buildings were meticulously formed to capture global admiration, playing a pivotal role in the Cold War battle for ideological supremacy.

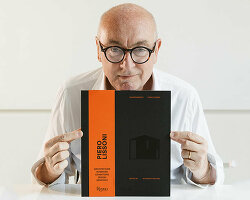

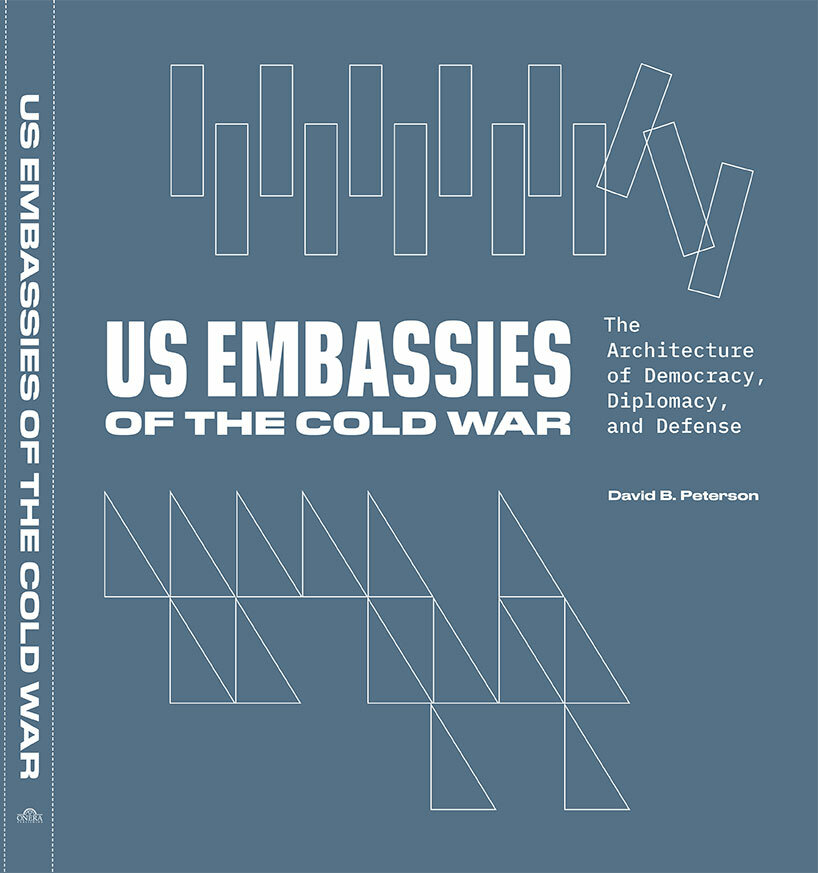

Delving into this narrative, David B. Peterson presents US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy and Defense, a new large format, photo-driven architecture book that highlights the fourteen most significant midcentury modern American embassies built during the Cold War. Scheduled for release on Tuesday, September 19, 2023, the 171-page hardcover book contains over 200 previously unpublished archival images of mid-century diplomatic buildings. For a comprehensive understanding of US embassy architecture, its significance in portraying national identities, and bridging cultural divides, designboom spoke with author David B. Peterson. Read the interview in full, below.

US embassy in Dublin | image courtesy of the Department of Drawings and Archives, Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, c.1957

Interview with David B. Peterson

designboom (DB): ‘During the Cold War, modern architecture was actively used as a powerful form of cultural diplomacy by the State Department’. Can you elaborate on specific design elements or features in these embassies that were deliberately incorporated to convey certain messages to foreign visitors and locals?

David B. Peterson (DBP): The midcentury modern embassies built by the US State Department between 1948 and 1962 were literal billboards – cultural diplomacy in a physical form that often included International Style features: ribbon windows, flat roofs, extensive glass and limited (if any) ornamentation.

The building’s circulation was also deliberately open and accessible for visitors to learn more about the United States and not simply a place for visas. These embassies frequently had separate entrances for the library, auditorium, and visas, all designed to maximize public access. In these spaces, local communities were invited to consume American culture in the form of books, magazines, cinema, art exhibitions, lectures, and a wide range of other media.

To complement their programming, the buildings themselves were also works of art – designed by many of the most prominent modernist architects working in the United States during this era. As one diplomat said: ‘the image of open Democracy was projected by American architects and designed through buildings which literally jeered the bunkers of totalitarians.’

US embassy in Dublin | image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania

DB: The architects who designed the US embassies during the Cold War were some of the most influential figures of the twentieth century, including Walter Gropius, Marcel Breuer, Eero Saarinen, Edward Durell Stone, and more. How do you think their architectural styles and design choices contributed to expressing American ideals of a progressive, democratic society?

DBP: Until the US State Department embarked on the post-World War II building program, a ‘typical’ American embassy would be difficult to describe. In most cases, embassies were housed in rented spaces on an ad-hoc basis.

By the end of WWII, neoclassicism had come to be widely associated with fascism– beginning with Mussolini and Hitler and continuing with Stalin. By designing the United States’ first purpose-built embassies in an explicitly modern language, and by building them on such a wide scale in the victorious exuberance of the post-war American moment, the State Department was seeking to differentiate American culture from fascism and communism. By embracing modern designs (including, in effect, glass curtain walls) America was promoting the benefits of an open, modern, and progressive nation– a far cry from neoclassicism. Some have characterized the decision by the U.S. State Department and its Foreign Buildings Operations as a battle of ‘the curtain wall vs. the Iron Curtain.’

It’s not likely a coincidence that Walter Gropius, the architect of the US embassy in Athens (the birthplace of Western democracy), was the founder of the Bauhaus, which was shut down by the Nazis in 1933. An interesting footnote, Gropius used the same Pentelic marble in the Athens embassy as was used to build the Parthenon.

US embassy in Athens | image courtesy of the Harvard Art Museums, c. 1956

DB: Architecture often reflects the cultural identity of a nation. Did you notice any instances where the design of these embassies sparked debates or controversies, either domestically or internationally, due to cultural differences or perceptions?

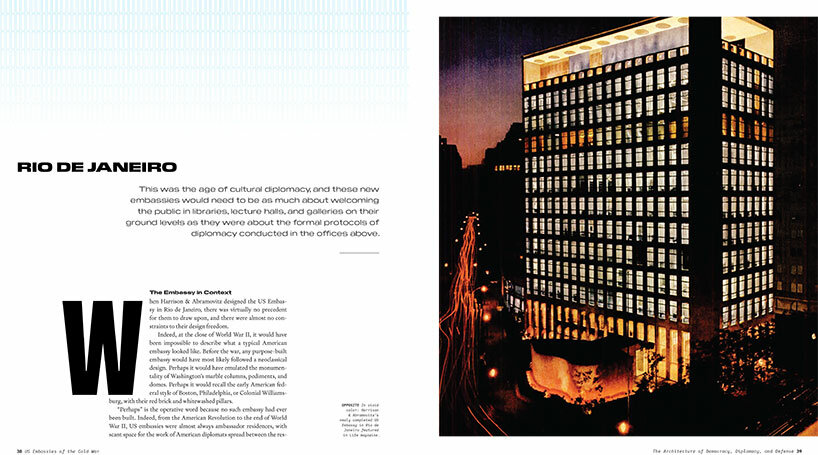

DBP: The modern embassy program sparked debates both in the US and in the places where they were built. The earliest embassies, designed by Harrison & Abramovitz in Latin America and Rapson & Van Der Meulen in Scandinavia, exemplified the extreme minimalism of the International Style. Congressional conservatives in Washington absolutely hated these buildings, resulting in a mid-1950s shift in the leadership of the program and a wider selection of architects who were charged with producing designs that were more sympathetic and harmonious with local contexts. The results were interesting but did not always win over critics.

US embassy in Rio | image by US Department of State, c. 1951 courtesy of the National Archives

DBP (continued): In Europe, these embassies were often built in dense, historic city centers on land only made available as a result of aerial bombardment during World War II. For example, Saarinen’s London embassy was built in the predominantly 18th-century Grosvenor Square. Saarinen strove to balance modernist principles with the local context by harmonizing the fenestration with neighboring Georgian buildings and by adding a monumental gilded eagle to the principal façade (designed by Theodore Roszak). The London press was scathing, especially about the eagle. The eagle, somewhat surprisingly, still hangs above the main entrance of the now decommissioned building, soon to open as a hotel and restaurant.

The Dublin embassy, designed by John Johansen in 1957, almost did not get built. Two US Representatives, Wayne Hays and John Rooney, complained vehemently that the design was not reflective of the United States and that the projected cost was too expensive. It took personal involvement from President Kennedy, who intervened to resolve the controversy. The embassy opened in 1964 and is expected to be decommissioned in the near future. Finally, even Florence Knoll’s furniture in the embassies was often criticized for being overly modern.

US embassy in London | image by US Department of State, c. 1956-1958 courtesy of the National Archives

DB: Diplomacy often involves engaging with diverse cultures and traditions. Were there any examples where the design of these embassies incorporated elements from the host countries’ architecture as a way of bridging cultural gaps?

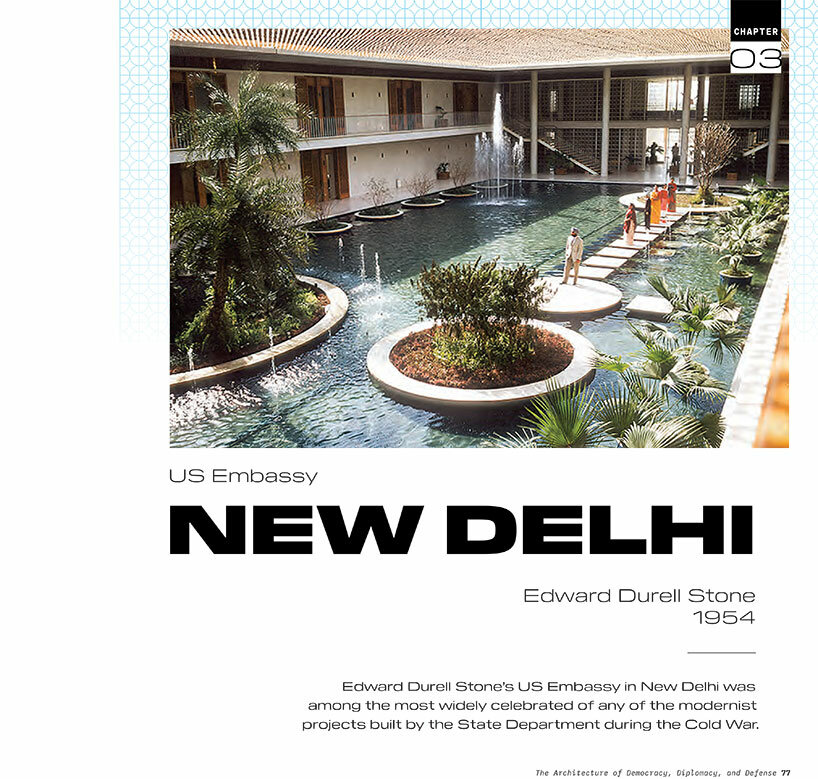

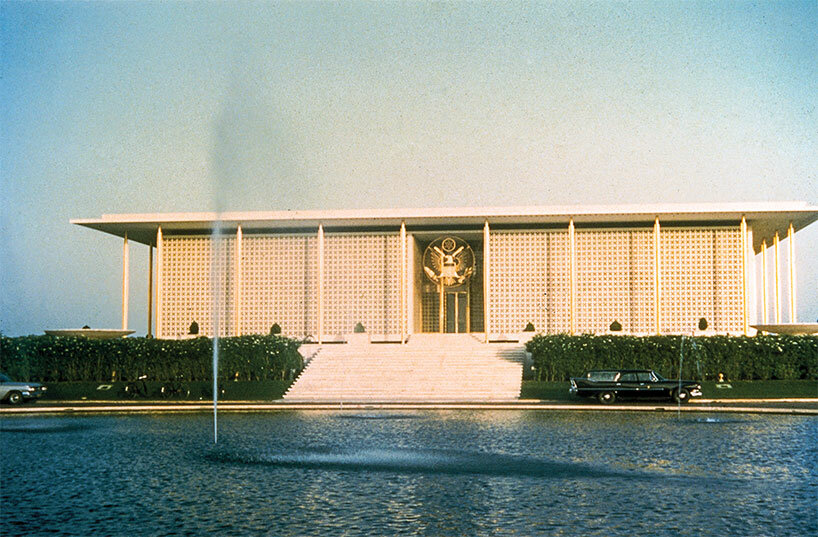

DBP: There were multiple instances where the architects involved in the program sought to incorporate local cultures and traditions in their designs. As I mentioned, Saarinen’s London embassy incorporated elements of Georgian architecture in an attempt to harmonize the design with its context in Grosvenor Square. Likewise, Edward Durell Stone modeled his chancery for the embassy in New Delhi on the Taj Mahal, complete with water gardens. In Accra, Harry Weese described his design as an inverted Wa-Naa Palace and used local mahogany extensively throughout the embassy. Dublin, the last embassy built under the program, was modeled on a Celtic fortress– moat and all. Johansen’s Dublin embassy has a circular footprint on a rectangular lot. The building’s round configuration was a symbol of openness and the democratic ideal of not turning its back on its neighbors.

US embassy in New Dehli | image by US Department of State courtesy of the National Archives, c. 1953

US embassy in New Dehli | image by US Department of State courtesy of the National Archives, c. 1953

DB: From the fourteen significant midcentury modern American embassies built during the Cold War, which three buildings stand out to you the most, and why?

DBP: Havana comes first because it’s one of the earliest Cold War embassies, completed in 1953. It was designed by Harrison & Abramovitz, the favorite architects of the Rockefeller family, and it was modeled on the United Nations in New York City (Wallace Harrison led the design team for the United Nations building. Harrison and Abramovitz also designed the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia). It embodies the highs and lows of American foreign policy during this era: on the one hand, it was designed as a symbol of optimism and international cooperation; on the other hand, it was hastily evacuated in January of 1961, not long after Castro’s revolution forced Batista to flee the country and just weeks before JFK’s Inaugural Address. Later in 1961, the Bay of Pigs fiasco was one of the early low points for the new Kennedy administration. And, of course, in October 1963 the world witnessed the near nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union, the Cuban Missile Crisis. Contemporary critics note that ‘the Havana building formed part of a string of sleek embassies commissioned by the State Department from prominent architects in the aftermath of World War II…having weathered the vicissitudes of US-Cuban relations, the Havana embassy building endures as a still functioning relic of Washington’s post-war bid to use modern architecture to project its image as a triumphant, dynamic superpower.’

US embassy in Havana

US embassy in Havana, furniture by Florence Knoll | image by US Department of State, c.1955 courtesy of the National Archives

DBP (continued): The second is London. Despite the controversy it faced, it was a masterpiece of modern design. Tragically, in recent years it has been gutted and altered virtually beyond recognition … highlighting the vulnerability of these historic buildings and the need to preserve them.

Finally, I would say New Delhi stands out because it was so successful. It was hailed in the press and widely beloved. It still serves as a US Embassy and just underwent a significant renovation to ensure its ongoing functionality. Frank Lloyd Wright described it as ‘one of the finest buildings of the last 100 years, and the only embassy to do credit to the United States.’

former first lady Jacqueline Kennedy at the US embassy in New Dehli | image courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, March 1962

DB: As the Cold War era recedes further into history, how do you think the legacy of these midcentury modern American Embassies continues to impact contemporary diplomatic architecture and the perception of American democracy abroad?

DBP: Perhaps the former Senator and Secretary of State John Kerry said it best a number of years ago: ‘We are building some of the ugliest embassies I’ve ever seen. We are building fortresses around the world…I cringe when I see what we are doing.’

In the post-9/11 world, with the widespread emphasis on security and defensive design, it is hard to imagine the spirit of optimism and openness in which these embassies were conceived. They represent a unique moment on the part of the United States to win international hearts and minds through the use of architecture, art, and the broader cultural outpouring of midcentury America.

After 9/11, the cultural diplomacy originally programmed in the US Embassies of the Cold War has all but disappeared. The days of art exhibitions, libraries and auditoriums are long gone. As one diplomat said: ‘After World War II, we were facing a world that was emerging out of a war and we wanted to use modern architecture as a way to convey our values, and a spirit of openness, optimism, democracy, and so we thought of architecture as a tool.’ The new US Embassy in London’s Nine Elms designed by Kieran Timberlake is often referred to as the ‘ice cube’ and it also has a moat around much of the building. I would call the recent embassy architecture ‘the identity crisis of the American Embassy.’

US embassy in New Delhi

DB: In recent times, the role of embassies has evolved, with advancements in technology enabling virtual diplomacy. How do you see the relevance of architectural diplomacy in today’s interconnected world?

DBP: President Eisenhower formed the United States Information Service (USIS) in 1953. Essentially, its mandate was to ‘tell America’s story to the world,’ as Eisenhower said. The Cold War embassies played an important role in communicating with host countries on the benefits of a free and open society through exhibitions, lectures and libraries. Now that public programming is no longer present in the embassies, America’s ‘story’ is mostly being communicated via the digital world.

The impact of architecture on diplomacy is certainly hard to quantify, but the impact of the midcentury Cold War embassies from personal experience is memorable. I was fortunate enough to get a tour of the US Embassy in Havana several years ago. While high perimeter security fencing is now in place when it was not originally, the building remains very similar to when it was completed in 1953. The openness of the design, the site location on the Malecon, and the structural system which eliminated interior columns give the building an inviting and engaging feeling. Sure, the travertine outer walls have been replaced as they did not perform well in Havana’s tropical climate. Mechanical equipment now sits on the building’s roof. The embassy was showcased in 1953 when the Museum of Modern Art held an exhibition called ‘Architecture for the State Department.’ Perhaps today, ‘starchitects’ design billboards mainly for art museums and corporations, which offer a different kind of architectural diplomacy!

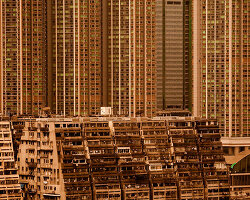

US Embassy in Caracas

US Embassy in Oslo

US embassy in Rio de Janeiro

US embassy in New Delhi

the cover of US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy and Defense

project info:

name: US Embassies of the Cold War: The Architecture of Democracy, Diplomacy and Defense

author: David B. Peterson

publisher: Onera Publishing

ARCHITECTURAL PHOTOGRAPHY (301)

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (260)

DESIGNBOOM BOOK REPORTS (182)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.